Το άρθρο βρίσκεται δημοσιευμένο εδώ. Για την ελληνική μετάφραση, διαβάστε παρακάτω, μετά το τέλος του αμερικάνικου.

In Athens, gentrification comes for the ‘birthplace of antifa’

Lucinda Smyth

Police at a riot in Exarchia in 2016 © Alex Majoli/Magnum Photos

Police at a riot in Exarchia in 2016 © Alex Majoli/Magnum Photos

Late September in Athens, and the air is still warm. Tourists roam the area around the Acropolis. There are bumbags and expensive sandals. Manicured fingers point towards shop windows. Along the Acropolis walkway, an old man plays “Zorba’s Dance” on a lute. Twenty minutes away, in Exarchia, things look different. Three giant dumpsters are on fire in the middle of the road. A line of at least 10 helmeted police stand in full riot gear, equipped with fire extinguishers, truncheons and shields. I walk cautiously past them and hear the clamour of smashing glass and shouting from a nearby street. An acrid odour fills the air. My eyes start to smart, and a harsh prickling creeps into my throat. Tear gas.

Exarchia, a neighbourhood known as a centre of leftwing activism in Athens, has links to anti-far-right groups dating back to at least the 1890s and is sometimes referred to as the “birthplace of Antifa”. In 1973, a student uprising at the Athens Polytechnic helped overturn the ruling military dictatorship. During Greece’s decade of economic convulsions after 2008, the square became a frequent site of protest. And following the influx of nearly a million migrants to the country in 2015, tens of thousands of refugees made homes in squats around the area.

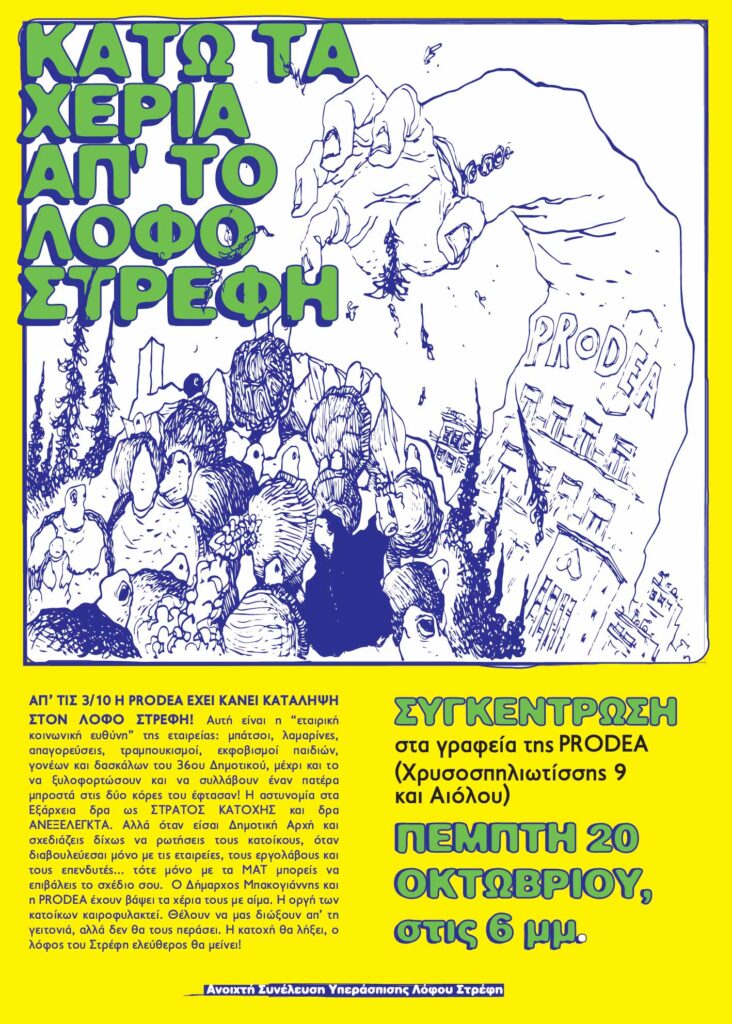

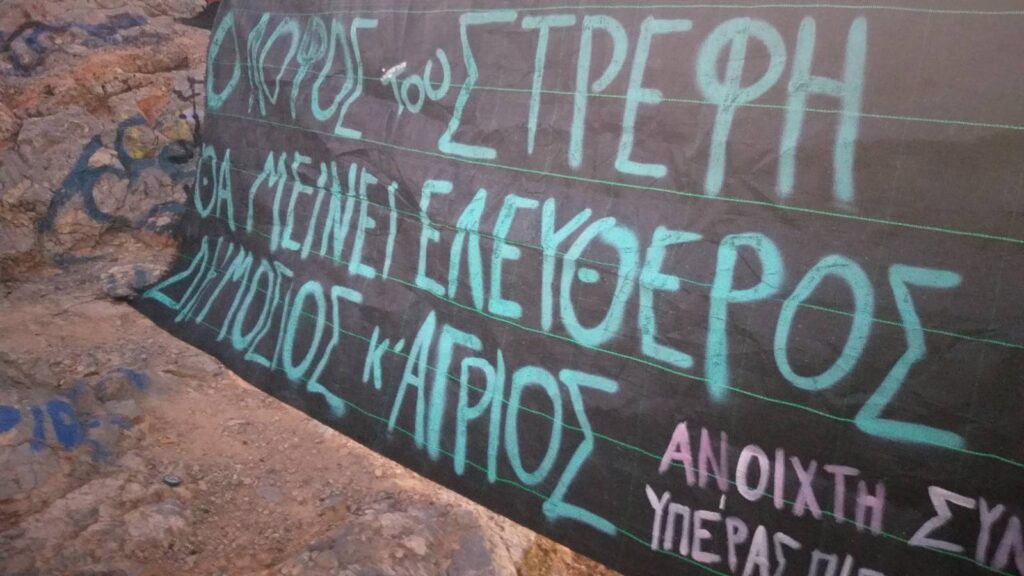

For decades, the neighbourhood was known as a place police rarely went. But recently, and especially this summer, that has changed. Following two new building projects — the construction of a metro station in Exarchia Square and the restoration of nearby Strefi Hill — the district has been flooded with police. Protests have raged in the face of what many locals feel to be an attack, gentrification as political weapon.

At the demonstration on September 24, an estimated 4,500 people have gathered to protest the metro construction. It’s just after 8pm when things escalate. Stones and heavy objects are thrown; tear gas canisters and flash bangs are set off by police. I turn away from the square and head in the opposite direction. A friend texts me not to go that way; the street beyond is filled with burning bins. Ducking down a side street, I reach the main road to the Archaeological Museum, next to the polytechnic. Banners are pinned along the railings of the university gates. They read “Burn the rich, not the witch” and “No to the metro”.

In August, trucks rolled into Exarchia Square early in the morning and turned the plaza’s core into a construction site, enveloped by a five-metre-high fence. Since then, it has been continually watched by about 50 police officers. Plans for what they are guarding have been circulating since the late 1990s. As part of the new Line 4, Exarchia metro station will connect the densely packed centre of the city with the suburbs, including Goudi in the east and Galatsi in the north. The construction has been the subject of political squabbling since it was given the green light in 2017, under the leftwing Syriza government. But the sudden appearance of a work site this summer was a turning point.

It follows what some have perceived as a push to erase the character of the neighbourhood by the centre-right New Democracy government. In 2019, during his successful campaign to become prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis promised a crackdown on crime, singling out Exarchia as a target. Citing drug activity in the area, he promised that he would “not let the neighbourhood become a den of illegality, troublemakers and drug trafficking”. Once his party came into power, police infiltrated the area and shut down all but one of its 23 anarchist and refugee squats. Since then, it has seen more police, more protests — and more tourists. Buildings have been sold off to short-term rental companies, rents have risen by 30 per cent and new bougie cafés and bars have popped up. Exarchia now has one of the highest numbers of listings on Airbnb and Booking.com across Athens. Stefania, an ex-photojournalist who lived in the area for 20 years, says it has acquired a new soundtrack: “The rolling wheels of Airbnb suitcases.”

A few weeks after the September protest, I revisit the square on a sunny Tuesday morning. Coffee shops are occupied by a few patrons, Greek voices mixing with American and British accents. The fence still stands in the centre, part sheet metal and part barbed wire, some of it painted with murals. I count at least 30 policemen within a 40-metre radius; it’s just after 9am. There’s an atmosphere of cautious calm.

I’m here to meet Hari, a 33-year-old architect who is a member of the local citizens’ group against the metro. About 10 of them have been coming here everyday to watch what is going on. “Otherwise they don’t tell us,” says Hari. She explains that she has been here since 7am. At 10am, many of the group will go to work, then come back after supper and continue their vigil until 11pm. They have been doing this every day since the site appeared. “This neighbourhood used to be so strong,” she says. “It was a home for so many people.” Not just anarchists, but the homeless, asylum seekers, artists and intellectuals. Now there is an atmosphere of overwhelming “hostility and fear”.

Residents like Hari oppose the construction for environmental reasons too. The square is one of the few green spaces in the district, and 72 trees are being destroyed to make way for escalators, ticket machines and lifts. Many residents have long argued there is a stronger case for building the station near the Archaeological Museum, where there is more space and because it is further from existing metro stations. There is precedent for such a change. In September 2021, a metro site was proposed in Rizari Park in the neighbourhood of Evangelismos that would have brought down 88 trees. Residents lobbied against it and, when shipping tycoon Nikos Pateras (who is also a local) spoke out against the proposal, the location was changed.

Exarchia doesn’t have access to influential connections. While the authorities argue the museum proposal is impossible due to construction problems and financial shortages, Hari feels the choice to put it in the square is a political decision. “This neighbourhood has just two public spaces,” she says. “When you’ve made a choice to build on both of them at the same time, it’s a choice to take them away from the neighbourhood.”

The appearance of the metro site coincides with another controversial development on nearby Lofos Strefi, a craggy hill with a view of the Acropolis. Tucked behind the Exarchia Steps, Strefi is a known site of late-night illegal activity, mostly drug dealing. But it is also a landmark green space in an otherwise built-up neighbourhood: a date-night spot, a place for residents to walk their dogs, a scenic viewpoint for tourists. There’s a primary school nearby and a basketball court at the foot of the hill.

In 2019, the municipality of Athens made a deal with Prodea, a real-estate investment company, to fund 49 per cent of a €2 million development here. The plans include building public toilets and installing rubbish bins, streetlights and flood protection, as well as improving walkways. Many residents see the agreement as a snub. For years, they have requested infrastructure improvements such as lighting and road upgrades and been ignored. Stefania tells me that residents have been excluded from conversations and left in the dark as to what exactly will happen to the site. “What we fear is that Strefi will become fenced off, closed to residents, and turn into a private park,” she says. Prodea did not respond to requests for comment.

I spoke on the phone to the mayor of Athens, Kostas Bakoyannis, who refuted these claims. “We don’t want to change the essential character of the neighbourhood,” he told me. “We want a mother to be able to push her baby on a stroller up Lofos Strefi hill and feel safe and enjoy the area. We want young people to be able to come to Exarchia on the metro and have a coffee or a beer.”

A week or so after the metro protest, there is another demonstration aimed at the Lofos Strefi development. Again, it turns violent. A video taken at the basketball court goes viral. It shows a man, one of the parents at the local primary school, being beaten by police in front of his eight-year-old daughter. The next day, at another protest for the same cause, an American photojournalist named Ryan Thomas is attacked by police while taking photos. The beating is caught on Thomas’s camera and in a video recorded by a journalist from his balcony. Almost everyone I speak to in the neighbourhood claims to have witnessed unprovoked beatings, catcalling, racist slurs or sexual abuse by police. According to the Greek ombudsman, complaints against police violence in Greece have risen 75 per cent since 2020. A Hellenic police spokesperson did not respond to requests for comment.

Crime rates in Athens are not high compared to other European capitals but they are increasing. The crackdown in Exarchia is broadly reflective of intensified security measures across the country. Prime minister Mitsotakis has followed through on his 2019 campaign to prioritise “law and order”. Shortly after coming to power, he overturned a law that forbade police from coming on to campuses. Introduced in 1982, eight years after the militia fell, the law was considered sacrosanct in Greece. Last year, Mitsotakis introduced a police unit specifically designed to patrol university campuses, which it began doing this summer. Mitsotakis argues that the unit is necessary to combat anarchist squats and gang activity. But many students feel it is an attempt to crack down on protesters and those who sympathise with socialists and asylum seekers.

Three kinds of police currently patrol Exarchia, including the DIAS, a motorcycle unit reintroduced under New Democracy. Riot police, known as MAT, are generally unarmed (when patrolling, one officer per unit carries a firearm), but they are conspicuously dressed in military green, with walkie-talkies and gas masks, black shin pads, shoulder protectors and heavy black rubber boots. All have batons, expandable metre-long cudgels with thick rubber handles, alongside large Plexiglas shields and white helmets.

In a country that was under military dictatorship a few decades ago, swaths of armed police can trigger unnerving memories. In September, 63-year-old popular singer Thanasis Papakonstantinou held a concert in support of the protests against the university police unit. Police came in; clashes ensued. Tear gas was used on the 5,000-strong crowd.

Bakoyannis, the mayor of Athens, is a central New Democracy figure with a keen interest in security. He’s also a vocal supporter of the changes taking place in Exarchia. In September, during a Live Q&A on Instagram, he repeated some of these sentiments to his 127,000 followers: “Lofos Strefi is very beautiful. But for many years it was cut off from the neighbourhood, and it was handed over to delinquency, illegality and the drugs trade. We are enacting this project to take back the space.” On Instagram, Bakoyannis cuts a confident figure. Describing himself in his bio as a “father, doer, dreamer”, a family man, he posts pictures of himself petting dogs and pushing a buggy. With his strong dark eyebrows and slightly curled mouth, he bears a passing resemblance to his uncle, prime minister Mitsotakis.

The events of this summer came at a contentious time for Mitsotakis and his party. He has been widely credited with boosting the economy and improving Greece’s image after the 2008-18 period. But a string of recent controversies, known as “Greek Watergate”, has scuffed his reputation. In July, Nikos Androulakis, the leader of opposition party Pasok, discovered that his phone had been installed with Predator spyware. It was traced back to the Greek secret service, which reports to Mitsotakis. Subsequent reports unearthed a network of wiretaps across the phones of Greek opposition politicians, as well as that of a finance journalist. Mitsotakis has denied knowledge and involvement. “The explanations were not sufficient, and that’s why I had to fire two people,” he recently told the Sunday Times. One of them was another of his nephews, Grigoris Dimitriadis.

Nevertheless, in a country where government mistrust is already rife, it has been damaging. Amid other criticisms, including a deterioration of press freedom under New Democracy and a series of illegal, deadly migrant pushbacks, some have interpreted the police crackdown as a way of appearing tough ahead of the elections in May. “The criminals of Athens are happy,” jokes Ilias, a café worker in Exarchia Square. “Now they can do what they want; they know the police are all here [instead].”

This summer was Greece’s most successful tourist season ever, with 2022 estimated to generate roughly €20 billion in revenue. The appetite for development is high, and some business owners in Exarchia are in favour of the changes. Christos (not his real name), 44, who runs a print shop off the square, feels the metro will provide good connections to the area. He lives outside the neighbourhood and complains of expensive fees for parking (€5 a day, as opposed to €1.50 for the metro). Christos has a side career as a musician and an affinity with the neighbourhood, having spent time here as a young man. But he also feels that the new influx of customers is a positive thing. “It is time to grow up,” he says. He references the metro systems in Paris and London by way of comparison and sees the developments, including Strefi, as an opportunity for the city to join the ranks of the rest of Europe.

The comparison with other European cities is a common refrain. A 42-year-old vegetable seller who has lived in and around the neighbourhood his whole life tells me it is usual for metro stations to be built in European squares. He is generally unbothered by the metro, feeling that the argument against it is “a little contradictory”. He points out that the neighbourhood is made up of students and that it will improve access to the university in northern Athens, which currently takes an hour by car due to traffic. “Exarchia is already gentrified. It’s not like it’s a poor area. The prices are already high. That’s the case in the whole of central Athens.” He says the protesters are “making a fuss. I hope it will die down soon.” That seems unlikely. The metro is predicted to take at least seven years to build, with estimated completion set for 2029-30. Until then, the police will stay. Protests show no signs of stopping.

In mid October, a basketball tournament is held on the court in Exarchia where the primary-school parent was beaten by police. A member of the local citizens’ group tells me the aim is to “take back” the space. I arrive at 7pm, when the scene is wholesome. People sit around with their dogs. Children play basketball on the court. A group of mothers from the primary school stage a feminist play. Periodically, streams of riot police patrol the area. They look the crowds up and down and eye my recorder suspiciously. About half an hour later, five motorcycles arrive — the DIAS — each carrying two helmeted, blue-clad police. KRS-One’s “Sound of da Police” booms out of the court’s sound system. The crowd chants “Exo!” — “Leave”. The basketball continues.

On the top of Strefi Hill, the scene is quieter. People are sipping beers and watching the sunset. I approach a couple on a date. Alexandra, 29, lives just off the square and says that she’d be fine about the metro if it was by the museum. But this is the first time she has felt unsafe in the area. In July, she didn’t leave her house for three days after witnessing a man being brutally beaten by police on her doorstep. “I wouldn’t use the term occupation lightly,” she says. “Because I know the implications. But that is what is happening here.” Now and then her eyes flit behind me. Two silhouetted policemen stand a few metres away. The whole time we’ve been talking they have been watching us.

Last weekend, hundreds of children and adult protesters formed a human chain around the site in the square, shouting “free the square”. Leaflets strewn all over the pavement read: “If one tree in the square is cut down, the centre of Athens will burn.”

On one of my last nights in Athens, I’m walking from dinner past the one remaining squat in Exarchia when I see two regular police officers talking to a group of tourists. An affable blond man in a Hawaiian shirt breaks off to tell me they are from Slovenia. They’re staying by the museum, he says and, having arrived an hour ago, were alarmed by the number of police here. In Slovenia, there are only this many around during sports fixtures or if someone important is staying nearby: “Is there something to be worried about? We’re here to have fun.”

He calls over to his friend, who is still drunkenly talking to the police and ignores him. The friend throws his empty plastic cup into a bin and carries on chatting. As I walk away, he is still there, talking and smiling, as the police nod and answer, occasionally smiling back.

Lucinda Smyth is the London producer at the FT Weekend podcast

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first